Charles Baudelaire

“On the Heroism of Modern Life,” from Salon of 1846

Charles Baudelaire, generally acknowledged as the most important French poet of the 19th century, also wrote influential essays, such as the article excerpted below, written in response to the official Salon of 1846. In this essay Baudelaire calls for artists to focus on their own time, rather than trying to recapture the ancient world, so revered by classicisism.

century, also wrote influential essays, such as the article excerpted below, written in response to the official Salon of 1846. In this essay Baudelaire calls for artists to focus on their own time, rather than trying to recapture the ancient world, so revered by classicisism.

In reading Baudelaire's essay below think about how it differs from the ideas of the defenders of official, academic art we encountered in the first day of the course. How did each think about the relationship between the present and the past? What did each value the most? What did each assume about the nature of art?

| Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867) |

|---|

Many people will attribute the present decadence in painting to our decadence in behavior. This dogma of the studios, which has gained currency among the public, is a poor excuse of the artists. For they had a vested interest in ceaselessly depicting the past; it is an easier task, and one that could be turned to good account by the lazy.

It is true that the great tradition has been lost, and that the new one is not yet established.

But what was this great tradition, if not a habitual, everyday idealization of ancient life - a robust and martial form of life, a state of readiness on the part of each individual, which gave him a habit of gravity in his movements and of majesty, or violence, in his attitudes? To this should be added a public splendor which found its reflection in private life. Ancient life was a great parade. It ministered above all to the pleasure of the eye, and this day-to-day paganism has marvelously served the arts.

Before trying to distinguish the epic side of modern life, and before bringing examples to prove that our age is no less fertile in sublime themes than past ages, we may assert that since all centuries and all peoples have had their own form of beauty, so inevitably we have ours. That is in the order of things.

All forms of beauty, like all possible phenomena, contain an element of the eternal and an element of the transitory - of the absolute and of the particular. Absolute and eternal beauty does not exist, or rather it is only an abstraction skimmed from the general surface of different beauties. The particular element in each manifestation comes from the emotions: and just as we have our own particular emotions, so we have our own beauty. . . .

But to return to our principal and essential problem, which is to discover whether we possess a specific beauty, intrinsic to our new emotions, I observe that the majority of artists who have attacked modern life have contented themselves with public and official subjects - with our victories and our political heroism. Even so, they do it with an ill grace, and only because they are commissioned by the government which pays them. However there are private subjects which are very much more heroic than these.

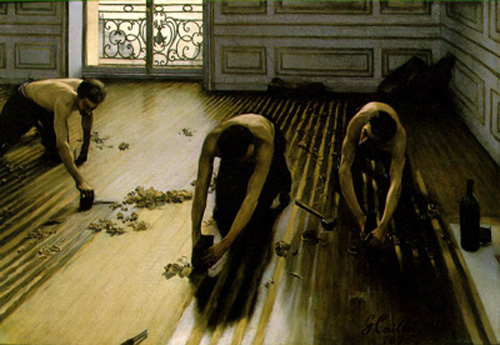

The pageant of fashionable life and the thousands of floating existences - criminals and kept women - which drift about in the underworld of a great city; the Gazette des Tribunaux and the Moniteur all prove to us that we have only to open our eyes to recognize our heroism. . . .

The life of our city is rich in poetic and marvelous subjects. We are enveloped and steeped as though in an atmosphere of the marvelous; but we do not notice it.

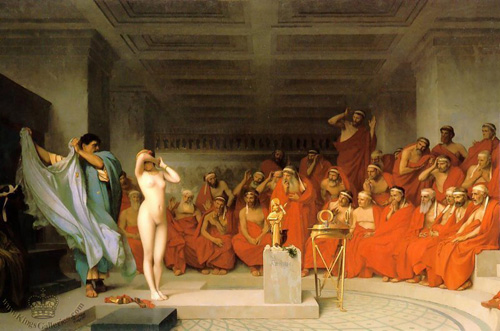

The nude - that darling of the artists, that necessary element of success -is just a, frequent and necessary today as it was in the life of the ancients; in bed, for example or in the bath, or in the anatomy theatre. The themes and resources of painting equally abundant and varied; but there is a new element - modern beauty. [ . . .]

Jean-Léon Gérôme, Phryne before the Areopagus (c. 1861)

Gustave Caillebotte, The Floor Scrapers (1875)

Camille Pissarro, Avenue de l'Opera, Place du Theatre Francais in Misty Weather (1898)